On DNA Day, we delve into the story behind Photo 51, arguably the most pivotal X-ray diffraction image ever captured. This photograph, born from pioneering scientific work, provided crucial evidence for deciphering the structure of DNA, the very blueprint of life.

DNA double helix structure, the molecule of life, as discovered with the help of Rosalind Franklin's Photo 51.

DNA double helix structure, the molecule of life, as discovered with the help of Rosalind Franklin's Photo 51.

The Genesis of Photo 51: A Basement Discovery

Photo 51 emerged in May 1952 from the meticulous work of Rosalind Franklin and her PhD student Raymond Gosling. Their laboratory was located in the basement of the chemistry building at the MRC Biophysics Unit, then part of King’s College London on the Strand. Franklin, a distinguished biophysicist, had joined the unit specifically to unravel the structure of DNA under the direction of Sir John Randall. Randall, head of the unit, had shifted part of the university’s physics department towards biological investigations.

The MRC Biophysics Unit later relocated to Drury Lane in the 1960s, eventually evolving into the Randall Institute. Today, its latest iteration is the Randall Centre for Cell and Molecular Biophysics at King’s College’s Guy’s Hospital campus. For those working at the Randall Centre, including X-ray crystallographers, Photo 51 holds profound significance, representing a direct lineage to groundbreaking work from the 1950s.

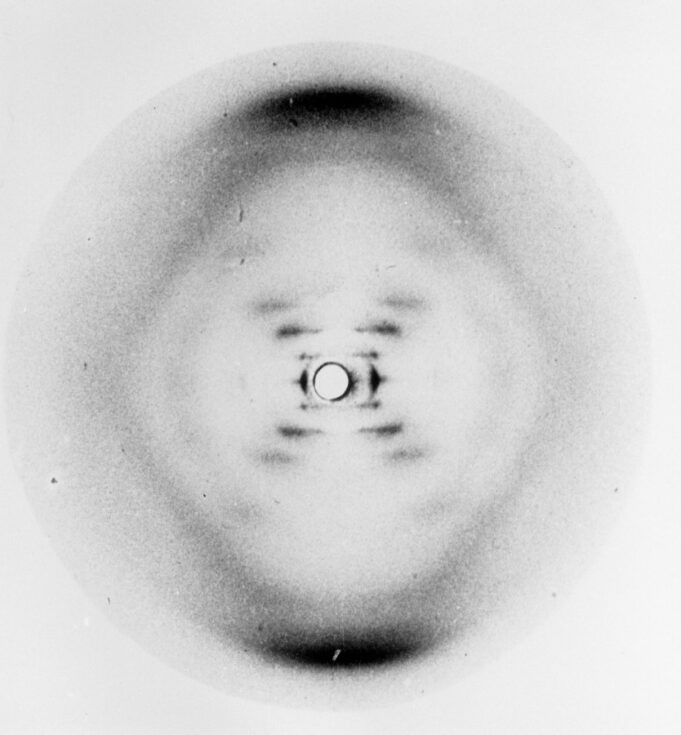

Rosalind Franklin's Photo 51, the groundbreaking X-ray diffraction image of DNA that revealed its helical structure.

Rosalind Franklin's Photo 51, the groundbreaking X-ray diffraction image of DNA that revealed its helical structure.

X-ray Crystallography: Illuminating the Molecular World

Photo 51 was created using X-ray crystallography, a well-established technique for determining the arrangement of atoms within molecules. In this method, molecules, arranged in a crystal or ordered form, are bombarded with X-rays. As X-rays interact with the electrons of the atoms, they scatter, producing a unique diffraction pattern. This pattern acts as a blueprint, allowing scientists to deduce the molecule’s structure. Modern X-ray crystallography utilizes thousands of images from different angles and sophisticated software to construct detailed 3D models.

The Painstaking Process Behind Photo 51

In the 1950s, while the fundamental principles of X-ray crystallography remained the same, the process was considerably more laborious. Franklin and Gosling employed highly purified DNA, mastering the delicate art of drawing it into fine strands suitable for analysis. Each strand contained countless DNA helices aligned in parallel.

The DNA strand was carefully mounted on a support and sealed within a specialized camera, positioned in front of X-ray film. Exposure to X-rays lasted for extended periods, sometimes days. A notable, and somewhat hazardous, aspect of their setup involved bubbling hydrogen through water into the camera to prevent X-rays from scattering off air molecules.

After development, the X-ray film revealed diffraction patterns. Raymond Gosling often reminisced about the excitement of witnessing these patterns emerge in the darkroom beneath King’s College.

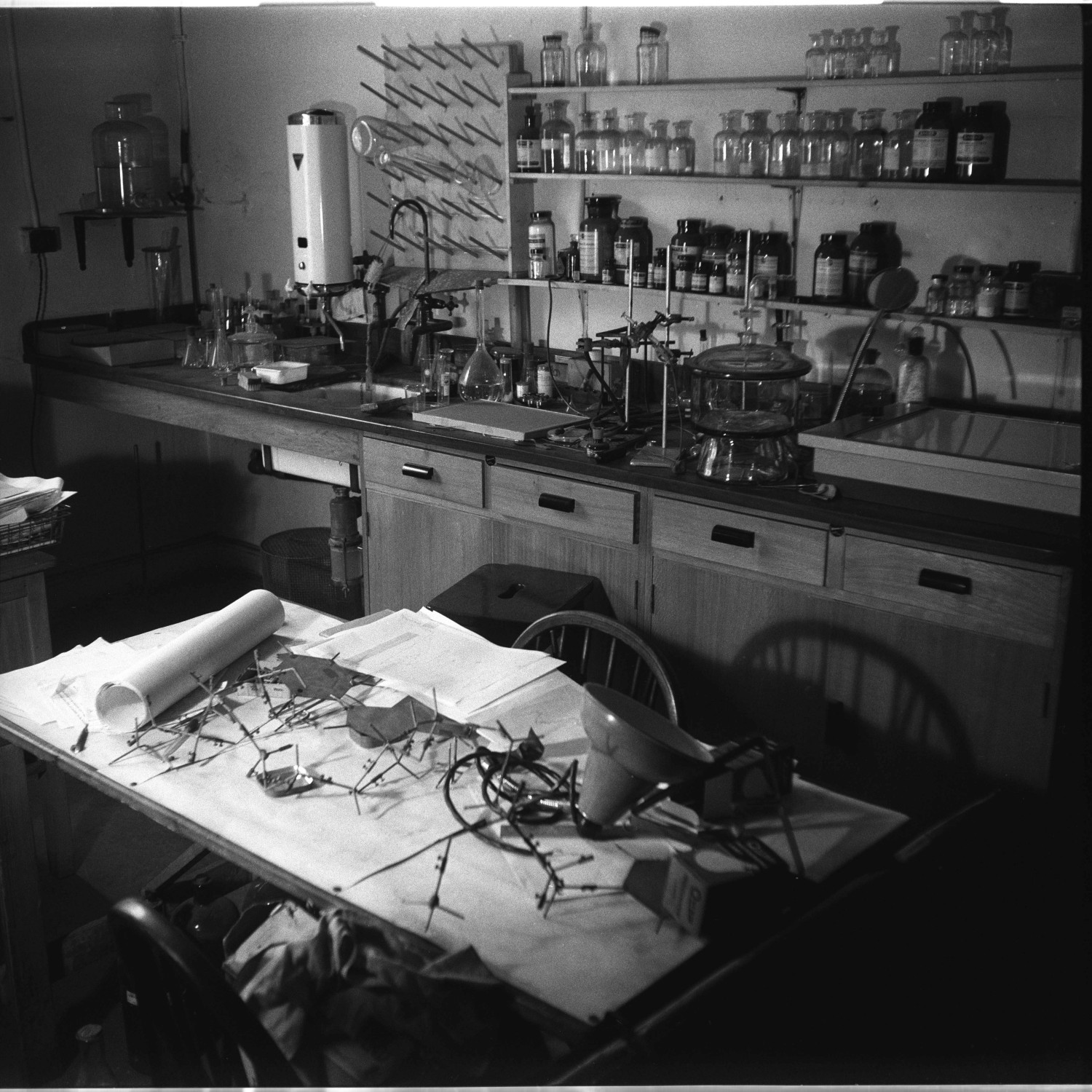

Rosalind Franklin at her lab desk at Birkbeck College, where she continued her pioneering work in molecular biology after Photo 51.

Rosalind Franklin at her lab desk at Birkbeck College, where she continued her pioneering work in molecular biology after Photo 51.

Deciphering Photo 51: A Glimpse into DNA’s Structure

Photo 51 specifically captured the ‘B’ form of DNA, which is more hydrated. Franklin and Gosling were investigating the effect of humidity on DNA images. Photo 51 was obtained at a high humidity level of approximately 92%.

The darker areas in Photo 51 represent regions where the film was intensely exposed to diffracted X-rays, indicating repeating structural features within the DNA molecule. The prominent dark bands at the top and bottom of the image correspond to DNA bases, the fundamental components of the genetic code. Their darkness signifies the regular and repetitive arrangement of these bases.

By measuring the spacing between these dark bands on the film and considering the experimental setup (DNA-to-film distance and beam orientation), researchers could calculate the distance between the bases in the DNA structure.

The Cross Pattern: Revealing the Helix

The distinctive cross-shaped pattern of spots in Photo 51 was particularly revealing. For James Watson and Francis Crick, who were actively constructing DNA models, this cross was a clear indicator of a helical structure. Maurice Wilkins, who also worked on DNA structure, showed Photo 51 to Watson during a visit, igniting Watson’s enthusiasm.

The sharing of Photo 51 by Wilkins to Watson without Franklin’s explicit permission has been a subject of much debate. However, Wilkins had legitimate access to the photograph as part of Franklin’s research materials as she prepared to move to Birkbeck College. Wilkins’ motivation was to accelerate progress in determining DNA’s structure, driven partly by a desire for British scientists to precede Linus Pauling in the US.

The cross shape directly implies a helix because the arms of the cross are characteristic of the planes of symmetry in a helix when viewed from the side, representing the turns of the helix. Closer inspection of Photo 51 reveals approximately ten blobs along each arm of the cross before reaching the large dark band at the top.

This observation suggested that there are ten DNA bases stacked within each turn of the helix. The slight absence of one blob, the fourth from the center, further hinted at a slight offset between the two strands of DNA.

Why Not Franklin Initially? The Focus on A-Form DNA

Portrait of Rosalind Franklin, the brilliant biophysicist whose Photo 51 was crucial to understanding DNA's structure.

Portrait of Rosalind Franklin, the brilliant biophysicist whose Photo 51 was crucial to understanding DNA's structure.

It remains a question why Rosalind Franklin didn’t immediately propose the helical structure based on Photo 51. One likely factor is that she initially concentrated on X-ray images of the ‘A’ form of DNA, which is less hydrated. These A-form images appeared to contain more structural information, and Franklin aimed to directly calculate the structure from them, rather than relying on model building. Intriguingly, her analysis of A-form DNA did reveal a crucial detail: the two DNA strands run in opposite directions. However, neither Franklin nor others fully grasped the significance of this antiparallel arrangement until Francis Crick recognized its importance just before constructing their final DNA model.

Franklin shifted her focus to Photo 51 in early 1953. Her notebooks show that once she dedicated her attention to it, she extracted all the essential structural information it contained. It is highly probable that given more time, Franklin would have independently solved the DNA structure. Notably, Watson expressed surprise at Franklin’s quick acceptance of their model when she saw it, likely because she recognized its strong consistency with her own data.

The Legacy of Photo 51: Confirmation and Recognition

By the time Franklin and Gosling’s paper, featuring Photo 51, was published in Nature alongside Watson and Crick’s groundbreaking model, Franklin had already moved to Birkbeck College. Watson and Crick’s model, being a theoretical construct, required experimental verification. Maurice Wilkins undertook this task, constructing the first accurate physical model of DNA in the summer of 1953 and validating it against diffraction data, including Photo 51. The structure proved to be correct, its elegance and explanatory power undeniable.

Photo 51 stands as a testament to Rosalind Franklin’s experimental skill and insightful data collection. It remains a powerful image, encapsulating a pivotal moment in the history of biology and highlighting Franklin’s indispensable contribution to understanding the double helix structure of DNA.